THE TREASURES OF ST MARY'S

The items shown below are part of St Mary's history and heritage.

Please note that they are NOT available to view at St Mary's as they are stored securely off-site

The items shown below are part of St Mary's history and heritage.

Please note that they are NOT available to view at St Mary's as they are stored securely off-site

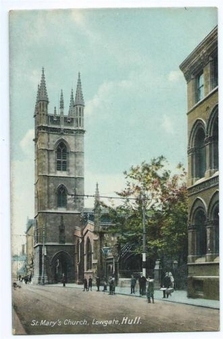

History & TOUR of St Mary's

(photographs by Angela Burkitt)

|

An opening prayer as you begin the tour

We adore you, most holy Lord Jesus Christ, here, and in all your churches Throughout all the world; And we bless you Because, by your holy cross, You have redeemed the world. The year St. Mary’s was first built on the present site is unknown. It originally belonged to the Priory at North Ferriby and is mentioned in a William Skayl’s will in 1327. It was at that time a Chapel of Ease to Ferriby. Archbishop Melton’s licence in 1333, which describes St. Mary’s as newly built, permitted the Austin (Augustinian) Canons of the Order of the Temple of the Lord of Jerusalem at North Ferriby to baptise, bury and take other services at the ‘Chapel of the Blessed Mary in Hull’. This made it a ‘church’ rather than a ‘chapel’. After the Reformation, St. Mary’s became an independent parish, but had the same patron as North Ferriby Parish Church until 1682. It was only legally separated from Ferriby and styled a vicarage in 1868. |

In Pevsner’s series The Buildings of England: Yorkshire and the East Riding, we read of a rebuilding taking place at the east end of St. Mary’s around 1400, which continued throughout the fifteenth century with the tower as the last work, and that bequests for the tower were made in 1449, 1504 and 1507, suggesting two phases. According to some accounts, the tower collapsed in 1518, demolishing the west end of the church and the present tower is the result of rebuilding in 1697. The tower and much of the church were built in brick with stone dressings. In 1826 the tower was encased in Roman cement made by Earles, a local firm. The present building now very much reflects the restoration work of 1861-3, carried out by Sir George Gilbert Scott.

St. Mary’s was one of the 476 churches with which Scott was connected between 1847 and 1878. Even though Scott was a major representative of the Gothic Revival, the restoration at Hull was less sweeping than many he had conducted. He endeavoured to retain as much of the mediaeval as possible at St. Mary’s.

Scott’s restoration scheme saw the brick tower encased in stone with windows of Gothic design added and the whole of the exterior encased in ashlar. Some of the old windows were reused in an added south aisle, but the east window and those of the north aisle had considerable portions removed. The south porch with its upper chamber was removed and the whole of the interior woodwork was swept away and replaced by pews. Some of this woodwork was incorporated into the paneling of the vestry.

St. Mary’s was one of the 476 churches with which Scott was connected between 1847 and 1878. Even though Scott was a major representative of the Gothic Revival, the restoration at Hull was less sweeping than many he had conducted. He endeavoured to retain as much of the mediaeval as possible at St. Mary’s.

Scott’s restoration scheme saw the brick tower encased in stone with windows of Gothic design added and the whole of the exterior encased in ashlar. Some of the old windows were reused in an added south aisle, but the east window and those of the north aisle had considerable portions removed. The south porch with its upper chamber was removed and the whole of the interior woodwork was swept away and replaced by pews. Some of this woodwork was incorporated into the paneling of the vestry.

The font of 1717 was replaced by one of Gothic design and a new altar table was made with a stone reredos i.e., the paneling behind the altar, set up behind it. At the west end, the old singing gallery was removed and the organ re-sited in the new aisle. The monuments were removed from the walls and piers of the church, and the old gravestones which paved the floor of the sanctuary moved out into the churchyard.

In short, under the direction of Scott’s restoration plan at St. Mary’s, an additional aisle was added to the south, a new vestry, porch and reredos were built, the tower was raised in height and encased in stone and all internal fittings – including altar, pulpit and font, were renewed.

The twentieth century saw two smaller, though equally significant, restorations at St. Mary’s – one in 1936-37 and more recently that of 2000-2007. At the restoration of 1936-37, the much decayed and badly weathered stonework was repaired and the nave and chancel roofs were re-leaded. In the 2000-2007 period, the pinnacles on the tower and worn stone were replaced and the clear clerestory glass also replaced. Part of the restoration also included the re-hanging of the bells on a new frame. Following a silence of almost fifty years, the bells finally rang out in 2002.

In short, under the direction of Scott’s restoration plan at St. Mary’s, an additional aisle was added to the south, a new vestry, porch and reredos were built, the tower was raised in height and encased in stone and all internal fittings – including altar, pulpit and font, were renewed.

The twentieth century saw two smaller, though equally significant, restorations at St. Mary’s – one in 1936-37 and more recently that of 2000-2007. At the restoration of 1936-37, the much decayed and badly weathered stonework was repaired and the nave and chancel roofs were re-leaded. In the 2000-2007 period, the pinnacles on the tower and worn stone were replaced and the clear clerestory glass also replaced. Part of the restoration also included the re-hanging of the bells on a new frame. Following a silence of almost fifty years, the bells finally rang out in 2002.

The Three John Scotts

Three Scotts of the same family served as priests at St. Mary’s during the 1800s. The first John Scott was born at Ravenstone near Olney in Buckinghamshire. He came from a family of evangelical persuasion and it is said he came to Hull as a result of certain connections. He was Lecturer at Holy Trinity in 1801. In 1816, the patron, Samuel Thornton, presented John Scott the living at St. Mary’s, where he served until his death in 1834. He was succeeded by his son also named John Scott.

The restoration of the 1860s, as mentioned in the History in Brief section, was initiated by the second John Scott. He called in his cousin, George Gilbert Scott, to carry out the work. Like his father, the second John Scott was an evangelical and even though the restoration followed a more high-church model, in that ecclesiological principles were incorporated, Scott did not depart from the accepted evangelical way of conducting services. There was still a sizable population in the parish at that time and the congregation numbered 500-600. John Scott did not live long enough to enjoy the newly restored St. Mary’s: he died in 1865 at the early age of 55.

Notably, five of the second John Scott’s sons, F.A. Scott, G.C. Scott, H. Scott, C. Scott and John Scott were part of the group of public schoolboys who founded Hull FC. Their father allowed the team to meet at the Young Men’s Fellowship and he also helped to run the Rifle Volunteer Group. It appears that F.A. Scott was the only playing member of Hull FC, being appointed Club Captain in 1870, with his brother, John, becoming Club President around 1879-80.

This son, the third John Scott, took up the living left by his father at St. Mary’s in 1865. He sought to make some changes and soon developed a devoted and focused congregation, making St. Mary’s not only a spiritual centre but also an initiator of social action in the parish. He set up a soup kitchen, a penny bank for the poor, and the funding of a parish nurse. John Scott was influenced by the Oxford Movement and, though mindful of his evangelical roots, paved the way for full catholic teaching and form, still practised at St Mary’s. John Scott placed great value on teaching: he instigated teaching missions and many guilds and brotherhoods for the instruction of people and for their sharing of religious life. In 1883, John Scott accepted the living of St John’s in Leeds. He stayed there until 1898 when he left for Wanstead, where he died in 1906.

Three Scotts of the same family served as priests at St. Mary’s during the 1800s. The first John Scott was born at Ravenstone near Olney in Buckinghamshire. He came from a family of evangelical persuasion and it is said he came to Hull as a result of certain connections. He was Lecturer at Holy Trinity in 1801. In 1816, the patron, Samuel Thornton, presented John Scott the living at St. Mary’s, where he served until his death in 1834. He was succeeded by his son also named John Scott.

The restoration of the 1860s, as mentioned in the History in Brief section, was initiated by the second John Scott. He called in his cousin, George Gilbert Scott, to carry out the work. Like his father, the second John Scott was an evangelical and even though the restoration followed a more high-church model, in that ecclesiological principles were incorporated, Scott did not depart from the accepted evangelical way of conducting services. There was still a sizable population in the parish at that time and the congregation numbered 500-600. John Scott did not live long enough to enjoy the newly restored St. Mary’s: he died in 1865 at the early age of 55.

Notably, five of the second John Scott’s sons, F.A. Scott, G.C. Scott, H. Scott, C. Scott and John Scott were part of the group of public schoolboys who founded Hull FC. Their father allowed the team to meet at the Young Men’s Fellowship and he also helped to run the Rifle Volunteer Group. It appears that F.A. Scott was the only playing member of Hull FC, being appointed Club Captain in 1870, with his brother, John, becoming Club President around 1879-80.

This son, the third John Scott, took up the living left by his father at St. Mary’s in 1865. He sought to make some changes and soon developed a devoted and focused congregation, making St. Mary’s not only a spiritual centre but also an initiator of social action in the parish. He set up a soup kitchen, a penny bank for the poor, and the funding of a parish nurse. John Scott was influenced by the Oxford Movement and, though mindful of his evangelical roots, paved the way for full catholic teaching and form, still practised at St Mary’s. John Scott placed great value on teaching: he instigated teaching missions and many guilds and brotherhoods for the instruction of people and for their sharing of religious life. In 1883, John Scott accepted the living of St John’s in Leeds. He stayed there until 1898 when he left for Wanstead, where he died in 1906.

Key Features of the Church

Tudor Wall Brass 1525

The Harrison Brass can be found in the Chapel of the Nativity. It is the only pre-Reformation monument that has survived at St. Mary’s and is an early example of an English brass plate (rather than a cut-out effigy). John Harrison, a notable benefactor of the church, was a ‘scherman’ or woollen draper who died in 1525.

The plate shows Harrison and his three sons in Tudor dress kneeling opposite his two wives. The inscription reads –

‘Here lyeth John Haryson Scherman and Alderman of this towne Alys & Agnes hys wyfes, Thom’s John and Wyll’m his sonis whyche John deceased the IX day of December the yere of our Lord MVCXXV on whose souls Jhu have mercy. Amen’.

Dobson Monument 1666 (over the north door)

William Dobson, whose monument over the north door depicts him wearing his ‘Citizen’s Gown’ and the mayoral chain, was a generous benefactor to St. Mary’s. He was twice mayor and one time sheriff of Hull. He died in 1666.

The Dobson Monument is an excellent alabaster wall monument. It is a frontal bust set in a classical arch, flanked by putti (cherubs) with cartouches of arms, skulls, swags and drops carved with fruit and flowers.

Stained Glass

The stained glass of St. Mary’s boasts a fine series of fourteen windows by Clayton and Bell 1866-c1900 forming one scheme: the north aisle depicting Old Testament subjects, the east end and southern aisle scenes from the life of Christ and the west end scenes from the life of the Virgin.

The East Window also designed by Clayton and Bell is dedicated to the memory of the second Revd John Scott. The window consists of seven main lights, showing the main scenes of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. The upper portion of the window bears intricate tracery of the apostles, the four evangelists, and the angels.

There are four shields of fifteenth century glass above the third and fifth main lights. They were removed from St. Mary’s at an unknown date and restored to their current position around 1870. The shields display the coats of arms of De la Pole quartered with Wingfield, Salisbury quartered with Neville, Henry VI, and Kingston upon Hull (the three coronets).

The Rood Screen

It is the Rood Screen that perhaps strikes the visitor most obviously on entering the church through the west door and is what, arguably, gives St. Mary’s its distinctive character.

The ornate perpendicular Rood Screen was designed by Temple Moore and made by Mr Gilbert Boulton of Cheltenham. This Rood (the crucifix with the figures of St. Mary and St. John) is the latest addition to the church and was erected in 1912. It was given anonymously in memory of Edward VII, whose likeness appears on the boss under the apex of the arch in the screen. It replaces a similar screen lost at the Reformation.

The pattern of the Screen is mediaeval and has ten bays, the two centre ones forming an entrance, which has a multi-cusped arch. The centre bays have doors and these and the dado of the screen are carved with tracery. The mullions of the screen are carried up into a groined cove enriched with ribs and carved bosses. The western side of the cross-beams shows ten angels bearing the instruments of the Passion.

The arms of the Rood Cross terminate in a fleur-de-lis, the emblem of Our Lady and each arm has a medallion, on which is depicted one of the evangelical symbols; the Man for St Matthew, the Ox for St Luke, the Lion for St Mark and the Eagle for St John. The four figures below the Rood are the four ‘Doctors of the Church’, St. Ambrose, St. Gregory, St. Jerome and St. Augustine of Hippo.

Other important features include the corbels of a King, Queen and Bishop on the north and south side of the chancel. These are considered to be the best pieces of sculpture in the church, and several memorials, notably the war memorial in the Chapel of the Nativity, which is, again, the work of Temple Moore.

Craftsmanship at St. Mary’s

Over the centuries many skilled tradesmen and craftsmen have been involved in the building, rebuilding, restoration and intricate decorative work of both the exterior and interior of St. Mary’s, carrying out commissions in wood, stone and metal.

Clayton and Bell

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient firms of English stained glass manufacturers during the latter half of the 19th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (London 1827-1913) and Alfred Bell (Stilton, Dorset, 1832-95). The company was founded in 1855 and continued until 1993. Their windows are found all over England, in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Clayton and Bell worked from large premises in Regent Street, London, where they employed about 300 people. During the late 1860s and 1870s the firm was at its busiest.

After the deaths of Alfred Bell in 1895 and John Richard Clayton in 1913, the firm continued under Bell’s son, John Clement Bell (1860-1944), then under Reginald Otto Bell (1884-1950) and lastly Michael Farrar-Bell (1911-93) until his death.

Clayton and Bell were masters of story-telling in stained glass. Many of their finest works are large multi-light church windows, depicting the most dramatic moments in the biblical narratives of the life of Christ. Although they were capable of producing rows of dour prophets, gentle saints and mournful crucifixions, what they excelled at was scenes of Christ bursting forth from the tomb, the descent of the Holy Spirit to the disciples and the archangel Michael calling forth the dead on the Day of Judgement.

Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878)

Sir George Gilbert Scott (cousin of the second John Scott) was born in 1811 in Gawcott, Buckinghamshire. He was first educated at home by his father, before studying with his uncle, the Revd Samuel King, at Latimers, near Chesham. In 1827, he became a pupil of the architect, James Edmeston. Following the death of his father in 1834, Scott went into partnership with a builder’s son he had met through his teacher, Edmeston, by the name of W.B. Moffat, to build workhouses. On the 5th June 1838, Scott married a second cousin, Caroline Oldrid.

In 1844, he achieved European reputation by winning the open competition for the design of the church of St. Nicholas at Hamburg. The style adopted for this building was in the style of German Gothic of the fourteenth century. The years between 1845 and 1862 were full of commissions and appointments for Scott, involving designs of new buildings, restorations, and inspection reports. In 1849, this included the important appointment as architect to the dean and chapter of Westminster Abbey.

In 1864, Scott was engaged in carrying out the Albert memorial, and the next year, designed one of his finest works, the station and hotel of St. Pancras. He regarded St. Pancras as the fullest realisation of his own vision of Gothic for modern purposes.

On 19th March 1878, Scott’s health began to fail and he died from a heart attack at his home in South Kensington on 27th March, 1878. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.

During his life he worked on 29 cathedrals, 10 minsters, 476 churches – of which, St. Mary’s is one – 25 schools, 58 monumental works, 25 colleges or college chapels, 26 public buildings, 43 mansions, and various small ecclesiastical accessories.

Two of Scott’s five sons, George Gilbert Scott, F.S.A (Fellow of the Society of Architects), and John Oldrid Scott, followed the profession of architecture, and completed some of the works left unfinished at their father’s death.

Temple Moore (1856-1920)

Temple Lushington Moore (1856-1920), architect, was the eldest son of Captain George Frederick Moore (1818-1884). He was born on 7th June at Tullamore, King’s Country, Ireland, where his parents were then living. In 1872, the boy, whose health was delicate, was sent as a pupil to the Revd Richard Wilton of Londesborough, Yorkshire. Three years later Moore was articled to the architect George Gilbert Scott junior, son of Sir George Gilbert Scott, and his career remained closely bound up with Scott for several years.

In 1884, following a long engagement, Moore married Emma Storrs Wilton (1856-1938), elder daughter of his former tutor. Family and clerical contacts in Yorkshire remained important to Moore and explain many commissions, especially during his early career. By about 1890 his reputation had grown rapidly and over the next twenty-five years he built some forty churches, which established him as England’s leading ecclesiastical architect from the mid-Edwardian years. He was Anglo-Catholic and much of his work was for high-church clients who required beautiful settings and fine furnishings for worship.

Although primarily a church architect, Moore undertook over seventy commissions for other types of buildings types, especially during the early part of his career. Major works include; South Hill Park, near Bracknell, Berkshire (1891-8), the ‘Eleanor Cross’ at Sledmere, Yorkshire (1896-9), and the Hostel of the Resurrection in Leeds (1907-28).

Moore died at his home in Hampstead on the 30th June, 1920, and was buried at St. John’s, Hampstead. He had intended that his only son, Richard, who had been articled to him c 1913, should take over the family business. Richard, however, died in 1918, and the following year Moore took on his son-in-law, Leslie Thomas Moore. Leslie continued in practice, often carefully adding to and furnishing his father-in-law’s former works, until the mid-1950s.

There are so many more hidden gems. For an example, the inscription on the tenor bell, reads:

`When first we draw our vital breath we enter into living death when souls are from their bodies torn `tis not to dey but to be born’

A closing prayer at the end of your tour

The Lord bless you and watch over you,

the Lord make his face shine upon you

and be gracious to you,

the Lord look kindly on you

and give you peace.

May the Lord bless you.

The Harrison Brass can be found in the Chapel of the Nativity. It is the only pre-Reformation monument that has survived at St. Mary’s and is an early example of an English brass plate (rather than a cut-out effigy). John Harrison, a notable benefactor of the church, was a ‘scherman’ or woollen draper who died in 1525.

The plate shows Harrison and his three sons in Tudor dress kneeling opposite his two wives. The inscription reads –

‘Here lyeth John Haryson Scherman and Alderman of this towne Alys & Agnes hys wyfes, Thom’s John and Wyll’m his sonis whyche John deceased the IX day of December the yere of our Lord MVCXXV on whose souls Jhu have mercy. Amen’.

Dobson Monument 1666 (over the north door)

William Dobson, whose monument over the north door depicts him wearing his ‘Citizen’s Gown’ and the mayoral chain, was a generous benefactor to St. Mary’s. He was twice mayor and one time sheriff of Hull. He died in 1666.

The Dobson Monument is an excellent alabaster wall monument. It is a frontal bust set in a classical arch, flanked by putti (cherubs) with cartouches of arms, skulls, swags and drops carved with fruit and flowers.

Stained Glass

The stained glass of St. Mary’s boasts a fine series of fourteen windows by Clayton and Bell 1866-c1900 forming one scheme: the north aisle depicting Old Testament subjects, the east end and southern aisle scenes from the life of Christ and the west end scenes from the life of the Virgin.

The East Window also designed by Clayton and Bell is dedicated to the memory of the second Revd John Scott. The window consists of seven main lights, showing the main scenes of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. The upper portion of the window bears intricate tracery of the apostles, the four evangelists, and the angels.

There are four shields of fifteenth century glass above the third and fifth main lights. They were removed from St. Mary’s at an unknown date and restored to their current position around 1870. The shields display the coats of arms of De la Pole quartered with Wingfield, Salisbury quartered with Neville, Henry VI, and Kingston upon Hull (the three coronets).

The Rood Screen

It is the Rood Screen that perhaps strikes the visitor most obviously on entering the church through the west door and is what, arguably, gives St. Mary’s its distinctive character.

The ornate perpendicular Rood Screen was designed by Temple Moore and made by Mr Gilbert Boulton of Cheltenham. This Rood (the crucifix with the figures of St. Mary and St. John) is the latest addition to the church and was erected in 1912. It was given anonymously in memory of Edward VII, whose likeness appears on the boss under the apex of the arch in the screen. It replaces a similar screen lost at the Reformation.

The pattern of the Screen is mediaeval and has ten bays, the two centre ones forming an entrance, which has a multi-cusped arch. The centre bays have doors and these and the dado of the screen are carved with tracery. The mullions of the screen are carried up into a groined cove enriched with ribs and carved bosses. The western side of the cross-beams shows ten angels bearing the instruments of the Passion.

The arms of the Rood Cross terminate in a fleur-de-lis, the emblem of Our Lady and each arm has a medallion, on which is depicted one of the evangelical symbols; the Man for St Matthew, the Ox for St Luke, the Lion for St Mark and the Eagle for St John. The four figures below the Rood are the four ‘Doctors of the Church’, St. Ambrose, St. Gregory, St. Jerome and St. Augustine of Hippo.

Other important features include the corbels of a King, Queen and Bishop on the north and south side of the chancel. These are considered to be the best pieces of sculpture in the church, and several memorials, notably the war memorial in the Chapel of the Nativity, which is, again, the work of Temple Moore.

Craftsmanship at St. Mary’s

Over the centuries many skilled tradesmen and craftsmen have been involved in the building, rebuilding, restoration and intricate decorative work of both the exterior and interior of St. Mary’s, carrying out commissions in wood, stone and metal.

Clayton and Bell

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient firms of English stained glass manufacturers during the latter half of the 19th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (London 1827-1913) and Alfred Bell (Stilton, Dorset, 1832-95). The company was founded in 1855 and continued until 1993. Their windows are found all over England, in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Clayton and Bell worked from large premises in Regent Street, London, where they employed about 300 people. During the late 1860s and 1870s the firm was at its busiest.

After the deaths of Alfred Bell in 1895 and John Richard Clayton in 1913, the firm continued under Bell’s son, John Clement Bell (1860-1944), then under Reginald Otto Bell (1884-1950) and lastly Michael Farrar-Bell (1911-93) until his death.

Clayton and Bell were masters of story-telling in stained glass. Many of their finest works are large multi-light church windows, depicting the most dramatic moments in the biblical narratives of the life of Christ. Although they were capable of producing rows of dour prophets, gentle saints and mournful crucifixions, what they excelled at was scenes of Christ bursting forth from the tomb, the descent of the Holy Spirit to the disciples and the archangel Michael calling forth the dead on the Day of Judgement.

Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878)

Sir George Gilbert Scott (cousin of the second John Scott) was born in 1811 in Gawcott, Buckinghamshire. He was first educated at home by his father, before studying with his uncle, the Revd Samuel King, at Latimers, near Chesham. In 1827, he became a pupil of the architect, James Edmeston. Following the death of his father in 1834, Scott went into partnership with a builder’s son he had met through his teacher, Edmeston, by the name of W.B. Moffat, to build workhouses. On the 5th June 1838, Scott married a second cousin, Caroline Oldrid.

In 1844, he achieved European reputation by winning the open competition for the design of the church of St. Nicholas at Hamburg. The style adopted for this building was in the style of German Gothic of the fourteenth century. The years between 1845 and 1862 were full of commissions and appointments for Scott, involving designs of new buildings, restorations, and inspection reports. In 1849, this included the important appointment as architect to the dean and chapter of Westminster Abbey.

In 1864, Scott was engaged in carrying out the Albert memorial, and the next year, designed one of his finest works, the station and hotel of St. Pancras. He regarded St. Pancras as the fullest realisation of his own vision of Gothic for modern purposes.

On 19th March 1878, Scott’s health began to fail and he died from a heart attack at his home in South Kensington on 27th March, 1878. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.

During his life he worked on 29 cathedrals, 10 minsters, 476 churches – of which, St. Mary’s is one – 25 schools, 58 monumental works, 25 colleges or college chapels, 26 public buildings, 43 mansions, and various small ecclesiastical accessories.

Two of Scott’s five sons, George Gilbert Scott, F.S.A (Fellow of the Society of Architects), and John Oldrid Scott, followed the profession of architecture, and completed some of the works left unfinished at their father’s death.

Temple Moore (1856-1920)

Temple Lushington Moore (1856-1920), architect, was the eldest son of Captain George Frederick Moore (1818-1884). He was born on 7th June at Tullamore, King’s Country, Ireland, where his parents were then living. In 1872, the boy, whose health was delicate, was sent as a pupil to the Revd Richard Wilton of Londesborough, Yorkshire. Three years later Moore was articled to the architect George Gilbert Scott junior, son of Sir George Gilbert Scott, and his career remained closely bound up with Scott for several years.

In 1884, following a long engagement, Moore married Emma Storrs Wilton (1856-1938), elder daughter of his former tutor. Family and clerical contacts in Yorkshire remained important to Moore and explain many commissions, especially during his early career. By about 1890 his reputation had grown rapidly and over the next twenty-five years he built some forty churches, which established him as England’s leading ecclesiastical architect from the mid-Edwardian years. He was Anglo-Catholic and much of his work was for high-church clients who required beautiful settings and fine furnishings for worship.

Although primarily a church architect, Moore undertook over seventy commissions for other types of buildings types, especially during the early part of his career. Major works include; South Hill Park, near Bracknell, Berkshire (1891-8), the ‘Eleanor Cross’ at Sledmere, Yorkshire (1896-9), and the Hostel of the Resurrection in Leeds (1907-28).

Moore died at his home in Hampstead on the 30th June, 1920, and was buried at St. John’s, Hampstead. He had intended that his only son, Richard, who had been articled to him c 1913, should take over the family business. Richard, however, died in 1918, and the following year Moore took on his son-in-law, Leslie Thomas Moore. Leslie continued in practice, often carefully adding to and furnishing his father-in-law’s former works, until the mid-1950s.

There are so many more hidden gems. For an example, the inscription on the tenor bell, reads:

`When first we draw our vital breath we enter into living death when souls are from their bodies torn `tis not to dey but to be born’

A closing prayer at the end of your tour

The Lord bless you and watch over you,

the Lord make his face shine upon you

and be gracious to you,

the Lord look kindly on you

and give you peace.

May the Lord bless you.